Where and when do we eat?

- Time Use Survey data on eating out

- Looser patterns of mealtimes on weekends

- Eating alone and with others

- Occasions for eating out

- Less time spent at restaurants

- Income, age, attitudes and restaurant supply play a role in eating out

Koko dokumentti sivutettuna

About the author: Johanna Varjonen is Senior Researcher at the National Consumer Research Centre. The article was published in Finnish in Hyvinvointikatsaus 3/2012 (Finnish title: Sy�misen ajat ja paikat).

The mainstay of our eating patterns has for many years been the meal that we take at home with our families. However, our eating habits have changed over three decades. The wide spread of microwave ovens in the 1980s made heating up food effortless and set family members free to eat at different times, and ready-made meals released families from the necessity of cooking. This made the most time-consuming domestic chore easier. The most recent change is associated with eating out, which frees us from the necessity of planning meals and buying ingredients.

PREVIOUSLY, eating out in our free time was something exceptional. We did it to celebrate a special day, or it was a special occasion in itself. It still is all of these things today, but eating out has also become part of every-day life for many. Even the term we use is a reflection of the way eating out has diversified: eating out has become a general term, instead of the more limited concept of eating at a restaurant.

In this article, I will have a look at where and when we eat, and examine changes that have taken place in our habits. I will focus particular attention to eating out in our free time.1 Looking back in history, it is notable that the time perspective of only two decades in this study is rather short for an activity that surely is as old as humankind.

However, never has there been a time in Finland when as much food was available, just waiting to be grabbed and stuck into your mouth, as there is now – if only you have the money to pay for it. In addition to restaurants and other actual eating places, caf�s and kiosks have sprung up on the kerbsides and in shopping centres where you can stop and have sweet and savoury pastries, beverages, sweets, snacks and, in summertime, fresh berries, or where you can buy these items to take away. We are tempted by the pleasures of eating much more often now than we did even a decade ago.

Eating out is understood as a wider concept than dining at a restaurant, as eating out also includes snacking. In our study, eating out was defined not only as dining at a restaurant or other eating place in the traditional way but also take-away meals and snacks which are prepared and sold by catering service companies but which you can eat at home or, literally, out. On the other hand, snacks and ready meals sold at supermarkets were excluded from the study. In conventional empirical data, including Statistics Finland's Household Budget Survey and the Study on the Trends of Dining at Restaurants commissioned by the Finnish Hospitality Association MaRa, little attention has been paid to increased snacking, even if coffee and buns and fast food have always been reported separately. Statistics Finland's Time Use Survey, similarly, distinguishes between meals on one hand and coffees and snacks on the other, and also reports where the respondents ate.

Initially, I will discuss some background information on eating out based on earlier research literature. Next I will look at analysis results related to eating in Statistics Finland's Time Use Survey data from different decades. I will then move on to examine the reasons for and practices of eating at restaurants based on data from the Study on the Trends of Dining at Restaurants2, and finally I will sum up the results produced by various sets of data.

Eating out has, in particular, been studied in countries where the restaurant industry is stronger than in Finland as a result of older urban settlement or tourism. Economic theory argues that cooking will be outsourced the more frequently, the higher the income of a household. The studies confirm this presumption at a general level, but the association is not quite as straightforward as that. The dissimilarities manifest themselves differently in visits to various types of restaurants.

Income seems to play a role in choosing an expensive and high-quality restaurant, whereas it does not seem to have a major effect on visits to fast-food places, pizzerias or ethnic restaurants. The studies also indicate that participation in working life, a reasonably large income and higher educational standard of the person responsible for providing meals in the family, as well as a high degree of urbanisation of the family's place of residence, increase the likelihood of eating out. Both parents taking part in working life and the ensuing shortage of time motivate families with young children to favour fast-food restaurants, as waiting for the dishes to be prepared at traditional eating places takes too long. (E.g. Byrne et al. 1998; Olsen et al. 2000; Lankinen 2008.) Finnish families with children often eat at fast-food restaurants when they are travelling, in which situation it is important that the meal is served without delay (the Promotion Programme for Finnish Food Culture Sre 2009).

In recent years, scientists have become interested in links between eating at restaurants and national health. This has been sparked by concerns over increasing obesity in young people. Fast-food restaurants in particular have been in the line of fire. While they are commonly seen as serving unhealthy food, irrefutable evidence of a connection between them and obesity has not been easy to prove, as weight management is also affected by many other aspects of our eating habits and lifestyle choices. Scientists standing up for fast food stress the fact that if you have had a heavy meal at a restaurant, you are unlikely to eat any more when you get home, as might be the case if you had only had a light meal (Mehta & Chang 2008; Anderson & Matsa 2011).

Unlike many Southern European countries, we have a strong tradition of communal eating in Finland, including free school lunches and subsidised meals at workplace restaurants. In such establishments, the planning of menus has for many years been governed by nutritional guidelines drawn up by experts, which is why communal meals have tended to promote healthy eating, including the use of vegetables and salads.

Time Use Survey data on eating out

The need for energy is a baseline that guides our meal patterns. Breakfast, lunch, afternoon coffee or some other snack in the afternoon, dinner and evening snack are the backbone of the ordinary eating pattern in Finland, in which individual variations occur. All or some meals can be taken at home or outside the home. Time Use Surveys help to trace an overall pattern of eating, and to variable degrees, also of eating out. What matters here is, of course, whether eating out has been distinguished from other meals in time use classifications. Time use classifications should be as similar as possible from period to period to allow us to observe the change in a certain activity.

Eating out has not been one of these activities, and our changing attitudes to eating at restaurants is clearly reflected in the classification of data from various decades. Eating out can be traced in two ways: on one hand, through the classification of activities in time use data and, on the other, classifications showing where the activity took place. In data from 1979, eating out was not separated from other eating. The material from 1987−1988 is excellent, as eating out has been distinguished in the data both in terms of its duration and the pattern of activities. The two latest Time Use Surveys note the duration of time spent eating out, but to discover the patterns, we have to rely on location codes.

In the following sections, I will first describe the time spent on eating as a whole, and then discuss how meals are distributed over the hours of the day. Figure 1 shows that eating is a vital daily activity in which differences are minor from year to year. A slight increase in the time spent on eating appears to almost exclusively be due to an increase in the time used to drink coffee and have snacks.

Figure 1. Time spent eating in 1987−1988, 1999−2000 and 2009−2010. Min/day.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey

For the proportion of meals taken at home to those eaten out, see Figure 2. This Figure includes meals only, not snacks and the like. The group that eats outside the home the most frequently is those aged 20–24 years, who spend 60 per cent of the time they use for eating on having meals outside the home. Some 20 per cent of these meals are taken at a workplace or student restaurant, 20 per cent in another household and over 10 per cent at restaurants. The group that eats at restaurants most often, on the other hand, is those aged 25−34 years. There has been no change in this figure over the last twenty years. Eating at the workplace, on the other hand, has declined slightly in this age group. This may be the result of increased unemployment or having take-away meals at the workplace, as there has been no corresponding increase in eating at restaurants. We should note, however, that the Time Use Survey describes the time spent eating as an average per day, not as the number of meals had.

Figure 2. Where people have their meals by age group in 2009−2010. Share of all meals. Per cent.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey.

The high incidence of having meals in another household, especially among those aged 20−24 years, is an interesting feature. It is as common as eating at a restaurant, school or the workplace, and has even become more common in this millennium. Eating in another household presumably means going to your parents' for a meal, and perhaps also groups of friends who enjoy cooking together as a pastime. Those in the retirement age tend to eat at home. This age group hardly ate out at all in 1987−1988, while eating out accounted for over 10 per cent of the time they spent on eating in 2009−2010. While the time spent on having meals at home has declined clearly, this reduction has not been fully compensated for by eating out, however. As a matter of fact, the explanation may be that meals have been replaced by snacks. The time spent having coffee and snacks increases from 43 minutes to 55 minutes a day when we move from the age group 45−54 to those aged 55−64 years. Presumably, the regular meals had by people in the working age are partly replaced by snacks in the age group 55−64. In groups older than this, the time spent having snacks increases further by a couple of minutes a day.

Looser patterns of mealtimes on weekends

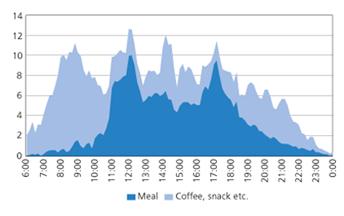

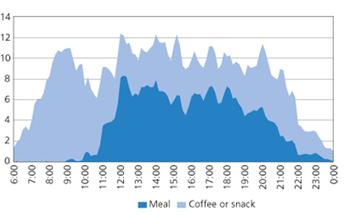

The pattern of meals has changed somewhat over the last few decades. On weekdays, the schedule of mealtimes is kept to a regular rhythm by eating at work, at a student restaurant or at school – similarly to our other daily rhythms. On the other hand, a major change has taken place in our eating patterns during the weekend. While we still had clear-cut lunch and dinner times in the late 1980s, all this had gone out the window by the turn of the millennium. The latest studies indicate that this change has been permanent. There is no consistent pattern, and we all have lunch or dinner whenever it suits us. Some of these meals are taken at restaurants, some at home. The share of snacks seems to have increased. This may indicate that we have become accustomed to only having a single proper meal on weekends. Breakfast and, to some extent, evening snacks stand out in the daily pattern, but otherwise somebody always seems to be snacking at any given time of the day. Figures 3 and 4 describe the pattern of mealtimes on Saturdays. The pattern for Sundays is rather similar to Saturdays.

Figure 3. Pattern of meals on Saturdays in 1987−1988. The share of respondents who were having a meal.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey.

Figure 4. Pattern of meals on Saturdays in 2009−2010. The share of respondents who were having a meal.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey.

The figures describe having a meal as the main activity, meaning that the person keeping a time use diary has specified eating as the primary activity rather than, for example, social interaction that may take place over a meal. We also analysed the time use data to discover how often eating had been recorded as a secondary activity. It turned out that having a meal was rarely a secondary activity, while having coffee or some other snack was entered as a secondary activity quite often, especially in the morning, when it was combined with reading the paper, and in the afternoon, when it may have been combined with work or social interaction. Men recorded eating as a secondary activity more often than women.

Eating alone and with others

Eating is considered a social activity, and meeting friends and offering hospitality are often given as the motivation for eating out. Drawing on data on spending time together with others in the Time Use Survey, I examined how often we eat with others. In Figure 5, spending time together is roughly classified into eating alone, with your spouse, with family members and/or acquaintances and only with acquaintances. No difference was made between having meals and snacks, and the figures include all types of eating that has been recorded as the main activity. Eating alone and together at different hours of the day was described by picking a ten-minute period at 30-minute intervals to include in the analysis. The analysis includes all participants of the Time Use Survey, or those aged 10 or over.

Figure 5. Eating alone and with others in 2009−2010. Percentage.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey.

At the points in time examined, on average 30% of the respondents ate alone, 24% with family members and acquaintances and 23% with either their spouse or acquaintances only.

Figure 5 shows that we frequently have our breakfast alone, our lunch with acquaintances, and our evening meal with family members and acquaintances, but one person out of five also eats alone. Eating alone is associated with living alone. Of those who took part in the survey, some 24% lived alone, 39% with a partner and 37% as part of some other type of a family.

Occasions for eating out

In this section, I will discuss the contexts and special features of eating out. I will draw on an analysis based on the Study on the Trends of Dining at Restaurants. The wishes and needs associated with eating outside the home are different depending on the situation in which people like to or have to eat out. I will discuss separately the way we eat on working days, in our free time and when travelling.

Eating on working days (including meals at schools, student restaurants and day-care centres) usually refers to a lunch that is recurrently taken in the same place. According to the study on the trends of eating out, some 40 per cent of all meals taken at restaurants were work related. The majority of those who ate at work, or 70 per cent, considered this a routine activity that was part of their day. Many also felt that it was easier to go out rather than, for example, bring a packed lunch. They also enjoyed the food at the restaurant of their choice. Food quality was, in fact, a key criterion for selecting a restaurant. The location of the restaurant has, however, become increasingly important in recent years, indicating that we also want the meals we take in our working time to be effortless.

Eating while travelling is associated with commuting (coffee, snacks), longer business trips or holiday travel. At those times we may eat breakfast at a hotel, fast food in the car, or even coffee while travelling on the metro and so on. Kiosks selling food are, consequently, placed at railway or bus terminals, and roadside restaurants built on major roads. Eating on the road considerably increases the proportion of eating outside the home. One respondent out of seven in the study on the trends of eating out had taken the last meal they ate out while travelling for business, and one fifth of meals eaten out in free time were taken while on a holiday.

Roadside restaurants established in connection with service stations typically are places where people stop on a journey to have a meal or a snack. People aged 50 or over and, in particular, those in the retirement age, use these restaurants relatively more than others. On the other hand, they were used less by managers and employees, as well as students. The respondent's place of residence also plays a role: those living in small towns and rural areas had meals at roadside restaurants more often than those living elsewhere. Contrary to what we might expect, people mainly had meals at roadside restaurants between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., and the most typical type of meal was lunch. It is possible that roadside restaurants have taken on the role of dining restaurants in the countryside.

Buying and having snacks is also a natural part of eating while travelling. Less than one half (43%) of the respondents in the study on the trends of eating out said they had bought snacks. The most typical reason was that they felt like a snack (32%) or did not have any other options (23%), which presumably means that the respondent did not have the possibility of eating a proper meal. The younger the respondents were, the more often their reason for buying a snack was that they felt like it. Kiosks and delis set up in places frequented by travellers encourage such needs with abundant stimuli.

Eating out in the free time often is an alternative to having a meal at home. Our most common reasons for eating out in our free time differ rather a lot from work-related reasons. Approximately one respondent out of three gave meeting friends or family members as the reason, and about one out of four cited entertaining and extending hospitality, which could be more easily and effortlessly done at a restaurant than at home. A significant share, or one fifth of eating out in the free time, took place while on a holiday.

The greatest changes in eating out in our free time are associated with the higher incidence of eating out at the weekends. Childless couples and those who live alone aged less than 45 eat out the most often, which is consistent with the figures for the previous decades. Childless couples eat out more often than before, as do parents of young children, as well as couples and those living alone aged 45 or over.

Less time spent at restaurants

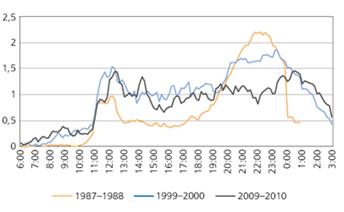

To conclude, I will examine social interaction at restaurants, as socialising often is associated with having meals and drinks. This is an activity to which the Time Use Surveys of all decades have paid attention. Changes in the category names are an nice reflection of how attitudes and behavioural models have changed. In 1979 and in 1987−1988, there were two categories of activities, titled Going to restaurants and dancing and Sitting in bars. A decade later, this activity was called Socialising at restaurants, pubs etc. and, in the latest study, Socialising at caf�s or restaurants.

At the national level, it seems that the time we spend at restaurants has declined steadily from what it was thirty years ago. This is the result of fewer people spending their time at restaurants. The slow but steady decline in the number of those engaged in this activity may also have been affected by a demographic change. In 1979, the large age groups were in their thirties and thus at an optimal age for spending time at restaurants. The time we spend at restaurants varies rather significantly depending on our stage in life, and this phenomenon has changed little over the decades. Even the latest study indicates that the heaviest users of restaurants, caf�s or pubs are young people (aged under 45) who live alone. They spend time at these establishments both during the week and at the weekend. Young childless couples spend a lot of time in restaurants and caf�s during the weekend, as do single parents. Couples aged 45 or over spend the least time socialising in restaurants, caf�s and pubs. In 2009−2010, they spent less than a minute a day on this activity, whereas those aged under 45 living alone spent 25 minutes on it.

Figure 6 shows the proportion of the population aged 10 or over that was at a restaurant at various times of the day. Socialising at a restaurant takes place in the evening, while having meals is more evenly distributed during the day. The figure describes the situation in the entire country and the average for all days. While on average, only one per cent of the population aged 10 or over spend time at restaurants, the figure is considerably higher on Saturdays. In the Helsinki Metropolitan area, this share varied between 5 and 9 per cent on Saturday evenings. However, Figure 6 describes a change in the role of restaurants over the various decades. In the late 1980s, people specifically went to restaurants to spend time and dance, whereas the time spent having a meal or socialising in a bar was considerably shorter than today. The evening was over around midnight, as this was the closing time for most places.

Figure 6. Distribution of visits to restaurants, caf�s and pubs over the hours of the day in 1987−1988, 1999−2000 and 2009−2010. Percentage of population aged 10 or over on an average day of the year engaged in this activity.

Source: Statistics Finland. Time Use Survey.

At the turn of the millennium, people were more likely to have a meal, and not just at lunch time. The time spent at restaurants in the afternoon was considerably longer than in the late 1980s, and people stayed out later at night. The latest Time Use Survey from 2009−2010 indicates that the time we spend in restaurants and caf�s is rather evenly divided throughout the day. Lunchtime and after midnight stand out as tentative peak times. Two peaks for having meals can be observed around lunch time. The latter is explained by the later meal times on weekends, in practice on Saturday. It appears that socialising at restaurants in the evenings starts even later than before and continues for slightly longer.

The differences between the weekend and weekdays in eating at restaurants are major in the Helsinki Metropolitan area and Northern Finland, but minor elsewhere in Finland. This is likely to reflect differences in the occasions of and the reasons for eating out. In the Helsinki Metropolitan area, it is easy to go out for a meal in your free time. On weekdays, eating out is likely to be mainly associated with working time.

Income, age, attitudes and restaurant supply play a role in eating out

The impressions of people who have meals outside the home created by the Time Use Survey and the study on trends of eating out are very consistent, regardless of the fact that the data are different. Eating at restaurants is very unevenly distributed among the population. The groups that eat out the most are young people in their twenties and thirties who live alone and childless couples, and the groups to eat out the least frequently are couples and those living alone aged 45 or over. Families with children are found between the two extremes. This change has taken place very slowly over two or even three decades. Childless young couples are eating out more often than ever. The ageing people do not seem to have returned to restaurants, even when they enjoy a good income and young children do not prevent them from going out. In this respect, however, signs of change can be observed. The frequency at which we eat out is thus affected by many other factors than just our income. It is possibly a question of both attitudes and the restaurant supply. Roadside restaurants have emerged as the place for eating out for rural areas and pensioners.

Sources:

Anderson, Michael L. & Matsa, David A. 2011. Are restaurants really supersizing America? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(January).

Byrne, Patrick J. & Capps, Oral & Saha, Atanu 1998. Analysis of Quick-serve, Mid-scale, and Up-scale Food Away from Home Expenditures. The International Food and Agribu siness Management Review 1(1).

Lankinen, Heikki 2008. Trenditutkimus 2008: Joka kymmenes ravintola-ateria nautitaan muualla kuin ravintolassa. Vitriini 8.

Mehta, Neil K. & Chang, Wirginia V. 2008. Weight status and restaurant availability – a multilevel analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34(2).

Olsen, Wendy Kay & Warde, Alan & Martens, Lydia 2000. Social differentiation and the market for eating out in England. International Journal of Hospitality Management 19.

Promotion Programme for Finnish Food Culture (Sre) 2009. Perhe ravintolassa. http://www.sre.fi/ruoka.fi/www/fi/tulokset.php.

Varjonen, Johanna & Peltoniemi, Ari 2012. Eating out as an aspect of changes in eating habits 1990−2010. Publications 1/2012. Helsinki: National Consumer Research Centre.

_______

1 This article is based on a study published by the National Consumer Research Centre in 2012 Varjonen and Peltoniemi: Eating out as an aspect of changes in eating habits 1990–2010. Publications 1/2012. National Consumer Research Centre.

2 The Finnish Hospitality Association MaRa handed over their data from 2008 and 2010 to the National Consumer Research Centre for the study referred to above. In the MaRa study, respondents aged 15 or over were asked if they had eaten at a restaurant in the two weeks preceding the interview. The results pertain to those respondents who had eaten out at least once in that period.

P�ivitetty 20.3.2013